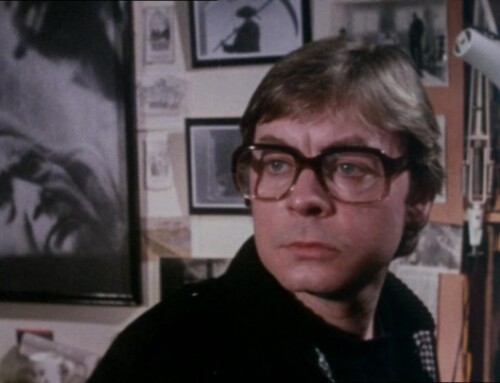

Sorrow Laughs

An appreciation of Simon Gray by Josphine Hart

Published here by kind permission of the author

Simon Gray wrote 40 plays -?? and a number of the wittiest diaries in the English language. He was nominated for and won countless awards -?? too many to list here -?? and anyway he would not have approved, having a healthy distrust of ‘??the arrogant oligarchy who merely happen to be walking around’. There was no kidding him and he knew that to write was to sit in judgement on oneself and mostly to find oneself wanting. Anything else was false. And false he never was. He wrote with the perfect poise of a poet, with his ear trained to our voice as he noted every lie. No playwright in modern theatre had a more finely tuned sensibility to the dangerous seduction of what Auden called ‘??the folded lie, the romantic lie in the brain’. In play after play, with scalding vertiginous wit, Simon Gray added to our store of uncomfortable self-knowledge: our terror of the abyss; the utter fragility of normal life; above all our often secret desire to be alone, endlessly thwarted as Larkin noted by the concept that ‘??Virtue is social’; and the torture of love when it turns to something else yet remains shadowed by its own loss. His art acknowledged, as we all must, that whatever personal courage or bravado we bring to it, however we attempt to swagger through it, the art of living and losing is harder than we pretend.

His characters were called into being during years of long nights fuelled by cigarettes and alcohol, alone, typing till dawn, on and on till the morning of ecstasy when a play was finished: ‘??This for me the only moment of pure happiness I ever experience in the playwriting business. I wish there was some ceremony, some physical ceremony to express it -?? picking it up, turning it upside down, slapping its rump, dishing out cigars…’ Plays are indeed a multiple-birth experience -?? to a perpetual life. In this art it is kinder than the experience it seeks to represent. And what characters he gifted us in those astonishing plays, beginning with jack, played by Alec Guinness, in Gray’??s wildly controversial debut Wise Child.

Ben Butley, in Butley, seemed to respond to Gray’??s Pirandello-like invitation, ‘??It’??s show time, folks’, and became, in Alan Bates’?? seminal performance, a terrifying Nietzschean figure, raging in his love-loathing, life-hating diatribes, culminating in a verbal marital flaying which would give Tarantino pause for thought.

In Otherwise Engaged, Simon Hench’??s icy heart beat out Sartre’??s mantra, ‘??Hell is other people’ with hilarious brutality until our laughter freezes in the waste of cruelty that is the last scene.

St John Quartermaine in Quartermaine’??s Terms can only whisper as his seemingly ordered life is almost stolen from him: ‘??Oh Lord!/Well – I say -?? / Oh Lord!’ It was the poetry of defeat (perfectly spoken) in a master-class from Edward Fox.

Close of Play starred Michael Redgrave as Jasper, a character whom, as Gray pointed out, lives in ‘??Hell buy discount xanax which turns out to be ‘??life, old life itself’??’.

Jameson, in The Rear Column, is one of five men isolated in the Congo ‘?- waiting, watching in Jeremy Irons’?? performance, as civilised behaviour, including his own, collapses. Geographically, the territory may have been alien -?? the moral issues remain the same -?? betrayal, particularly the betrayal of self, as demonstrated by six academics adrift, in their own way, on a literary magazine in The Common Pursuit.

In the heartbreaking Japes, the eponymous hero was played by Toby Stephens -?? his agonising disintegration witnessed by his appalled brother. Charles and Celia, the parents in The Late Middle Classes, are seemingly unaware of their son Holly’??s psychological growing pains during his dangerously sentimental education – one which will distort his soul forever. Their elective moral blindness destroys grace â?? as it almost always does in Gray’s universe.

This warning sounds out in all his plays. It is what gives them their moral tone. Attention must be paid to this above all else. No system is to blame -?? the fault lies in ourselves. Thus Gray’s work cuts along the nerve -?? a sometimes painful process. With his natural gift for comic timing, the soaring, thrilling laughter which drenches the plays was also his anaesthetic of choice. There was and is an artistic price to be paid. In the literary arts an almost Orwellian hierarchical system denies the accolade of greatness to work we designate as comedy. In this we are often wrong – forgetting that ‘??Excess of sorrow laughs/excess of joy weeps’.

There is a strange custom in contemporary theatre which ranks the political as of greater consequence than the examination of the human heart in conflict with itself. Truth is timeless, it has no accent and is beyond class and is as easily found in Moliere’??s court and Chekov’??s dying estates, in Rattigan’??s drawing rooms as in Gorky’??s lower depths. It lies in the interior and Gray was always on his way to the interior. The exterior was ever only the frame. His plays have little to say about the politics of the day. Arthur Miller shrewdly noted that before a play is -?? ‘??it is a kind of psychic journalism’, a mirror of its hour – and this reflection of contemporary feeling is precisely what makes many plays irrelevant to later times. What finally survives, when anything does, are archetypal characters and relationships which can be transferred to the new period.

Simon Gray left us a gallery of such characters to see us through life. Their vibrant nature, their thrilling command of language to torment, to seduce, to manipulate, will forever attract our best actors. Indeed few playwrights can number performances from so many artists whom one can truly describe as great. Nor can many boast that much of their work directed with such exquisite precision and celebration by one of theatre’??s seminal figures -?? fellow playwright and Nobel Laureate Harold Pinter: ‘Life in the theatre has not brought me anything more rewarding than directing Simon Gray’??s plays.’