On directing The Late Middle Classes

by David Leveaux

First published in the Independent on 24May 2010

In a moment of inexplicable buoyancy, I once told Harold Pinter, who was about to rehearse the role of Hirst in our production of his play No Man’s Land, that I thought it essential that we didn’t fall into being “Pinteresque”.

Looking back, I must admit it was a note that could have gone either way. Luckily -?? and perhaps not too surprisingly, given Harold’s energetic pragmatism when it came to the job in hand -?? he seemed really quite pleased.

Famous writers tend to attract adjectives the way whales attract barnacles. Pinter is invariably “enigmatic”, Stoppard “dazzling” and the great whale, Beckett, “existential” – something I imagine used to be rather a fun thing to be, but now means basically “bleak”.

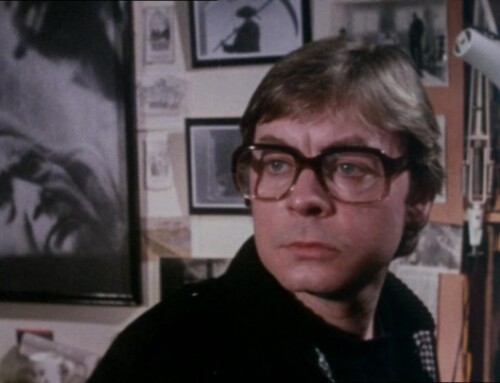

It’s been my great luck to be in a rehearsal room with all of the above, and the only thing I can say with certainty that they share is a general impatience with their adjectives, if only because those adjectives delay -?? or more often outright traduce -?? the main event. And to be fair, the particular barnacles that have attached themselves to these writers over time last about as long as useful commodities in the rehearsal room as an estate agent’s brochure on entering the house to which it actually refers. There isn’t, as far as I know, an adjective for Simon Gray.

And I have the feeling this is rather cunning of him, even though I also feel there ought to be one for someone who perhaps more than anyone captured the sheer hilarity, embarrassment and improbable heat under the ice of the English. His play The Late Middle Classes, which we are rehearsing for the Donmar in London, was originally directed by Harold Pinter in 1999 but was never seen in London after the West End producer took the cue from a critic to dump it for a show called BoyBand -?? which then closed in a few weeks. It’s the kind of thing I imagine Simon Gray being as funny about as he must have felt desolated about at the time.

So when the play alprazolam online came to me about two years ago, I got the rather guilty feeling that I ought to have known it already. And, on reading it, was instantly happy that I had not. Because what leapt off the page was the strangest, loveliest, fiercest account of a boy growing up in post- war England that was not nostalgic but did that thing that Coward at his best could do -?? give you the facts about a nation coming to terms with what we mean by victory. And the facts about sex under the defensive but desirously seeking radar of language.

I did not know Simon Gray. I met him only briefly. But now I wish I had known him. Victoria, his wife, remarked to me that he was “the funniest man in England”. And she said that with the kind of suddenness that managed to combine romance and the facts in one go.

What I do know is that he had the special gift of making the English language subversive. At once energetic, lethally penetrating, locally vulgar, and, in the high moments of passion, molten.

By coincidence, the heirs to the late middle classes he wrote about recently strolled through the gardens of Downing Street. But theirs strikes me as a dismally tinny echo of the troubled and passing world Simon nailed – and gave words to. Because his English was vibrant with purpose. Suspicious of the empty phrase, ruthless and spare and quite beautiful.

Samuel Beckett once referred to a favourite rugby fly-half as “capable of genius when the light is dying”. I think it’s an apt phrase for Simon’s evocation of a certain England. Not a phoney, sentimental version of it, by any means. In fact, one frequently outraged by its secrets and hypocrisy. But also one alive to the power and grace of the English language to demolish the often unspoken anxieties of incomprehension and cliche on which sentimental tyranny and ideology depend. In other words, he had a lovely way of using words to make you free -?? or to fall silent at all the moments that count. And who needs an adjective for that?